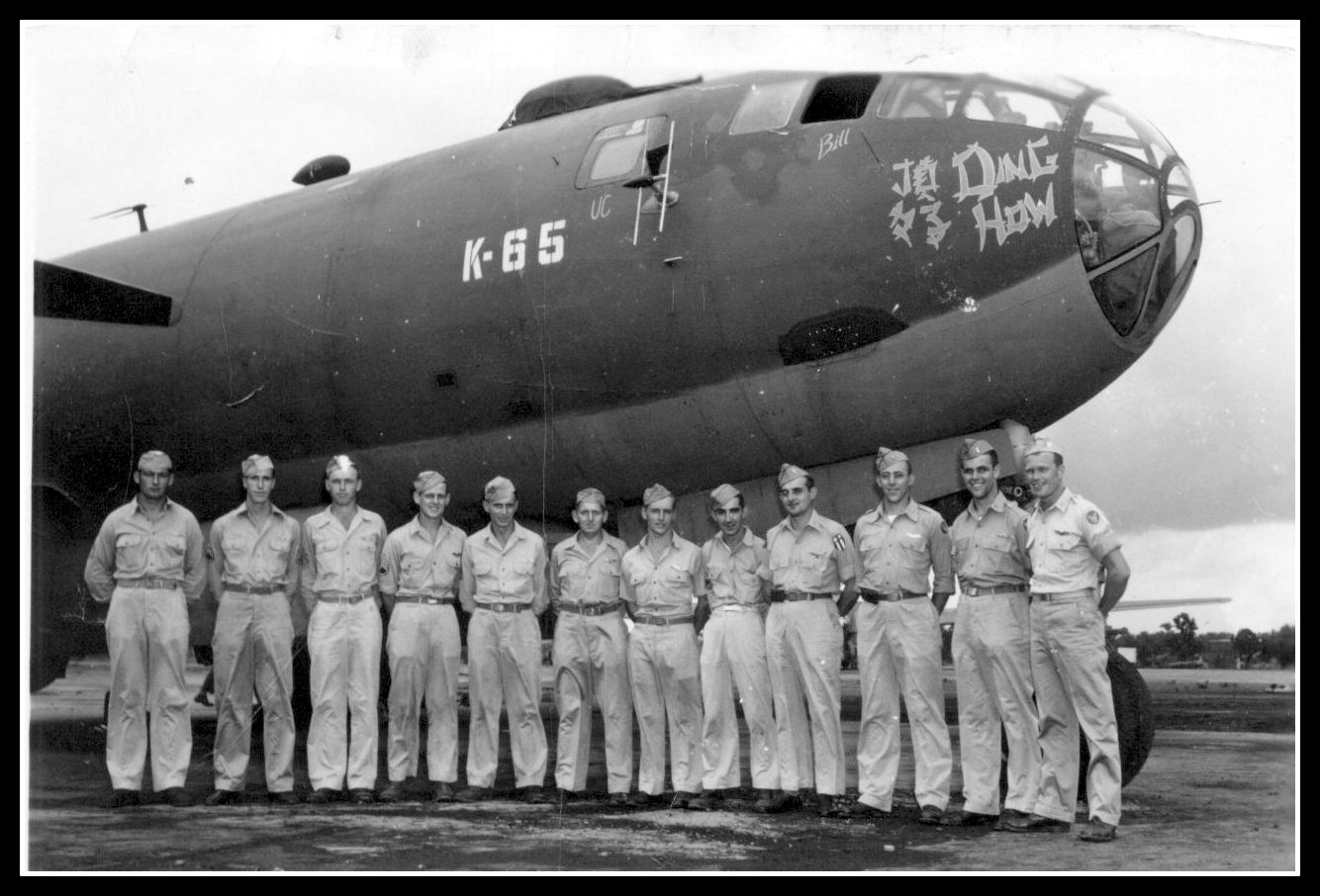

T-Sgt. Thomas Maxham, 444th Bomb Group |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The following information is courtesy of Mark R. Miller, son of Uline Miller, a crew member on Maxham's fatal flight.The Captain Nicolas VanWingerden Crew, B-29, China/Burma/India, 194420th Air Force, 58th Bomb Wing444th Bomb Group, 676th SquadronThe 58th Bomb Wing of the 20th Air Force was formed to consolidate the operation of the new B-29 bomber in the war against Japan. The 444th Bomb Group of the 58th Wing was first formed up in Marietta, Georgia, then moved to Great Bend, Kansas. In early April 1944, the 58th Wing moved to the China/Burma/India theatre. The India base of the 444th was in Dudhkundi, about 40 miles northwest of Calcutta; their forward China base was at Kwanghan, near Chengtu. The VanWingerden crew (Crew #12), flying aircraft 42-6225, "Ding How" were, along with the rest of the 444th Bomb Group, one of the first B-29 crews to see action against the Japanese in the China/Burma/India theatre in 1944. By October of 1944, this crew had flown eight "Hump" missions (over the Himalayas between India and China) and three bombing missions against enemy targets (Yawata, Japan, 15 June; Okayama, Formosa, 14 October; Omura, Japan, 25 October). All but three of the VanWingerden crew were lost on December 24, 1944, when their new aircraft 42-63458, "Wing Ding", crashed on takeoff from the Dudhkundi base in India. The survivors were VanWingerden, Miller and Warner.

20th Air Force, 58th Bomb Wing, 444th Bomb Group, 676th Squadron

The Captain Nicolas VanWingerden Crew, B-29, China/Burma/India, 1944 Accident in India 24 December, 1944 INTRODUCTION The following account is derived entirely from an accident report obtained from "Accident Reports" of Millville, NJ. Capt. Nicolas Van Wingerdenís crew (58BW/444BG/676BS), consisting of Co-pilot 1/Lt. William C. Jennings, Navigator 1/Lt. Wendell F. Geiwitz, Bombardier 1/Lt. Albert E. Woltz, Engineer M/Sgt. Uline C. Miller, Radar Operator T/Sgt. Thomas J. Maxham, Radio Operator S/Sgt. Samuel E. Davis, CFC Gunner S/Sgt. Kenneth C. Carlson, Right Gunner S/Sgt. Rex T. Phelps, Left Gunner S/Sgt. Martin T. Warner, and Tail Gunner S/Sgt. Scott C. Baker, had come to the CBI in olive drab aircraft 42-6225, "Ding How", but had recently been assigned a new aircraft, silver 42-63458, which may have been named "Wing Ding". A week after the accident, an inquiry was conducted, and the dialogue with the three survivors, Aircraft Commander Van Wingerden, Flight Engineer Miller and Left Gunner Warner, is included in the accident report, as well as written statements by the crewmen and other involved parties. THE STORY Itís about 5:05 in the morning (IST) of 24 December 1944 at APO215, India. Aircraft 458, under the command of Van Wingerden, readies for take-off to forward base A-3 in China with a load of 500-pound bombs. The aircraft is loaded with 6700 gallons of fuel, and the AC estimates the gross weight at 136,000 pounds. He likes this aircraft; it has just over 103 hours on it. In the control tower, Cpl. Louis F. Angelo gives taxi instructions. As they are taxiing, the AC calls the control tower for the last time to report that another ship is blocking their path but it is being towed out of the way. On the fire fighter line, Capt. Franklin C. David, Medical Corps, prepares to leave; it appears that this will be the last take-off this morning. Flight Engineer Miller notices that the cylinder head temperatures are all between 180 and 190 degrees, so he closes the cowl flaps down to 12 degrees, enabling a take-off with head temperatures straight across at 200 degrees. At the near end of the N.E. runway, all check lists are completed. Take-off is made about 5:27, with the right landing light partially extended, the co-pilot watching the ground and the bombardier calling off airspeed. The engineer has closed down the cowl flaps to 4 Ĺ degrees, and the cylinder head temperatures on the two high engines are not going over 235 and 240 degrees. After using less than 6,000 feet of runway, the ship is airborne with an air speed of between 130 and 135 mph. The AC goes onto instruments and corrects a slow turn to the left. He observes the climb indicator is showing 500 feet per minute, and the airspeed has slowly increased to 150 mph. The flight engineer hears the landing gear going up. He checks his instruments; everything looks normal, and the rate of climb indicates 500 fpm. The left gunner reminds him to turn on the landing gear lights. In the control tower, Cpl. Angelo observes what appears to be a normal take-off; he can see the navigation lights of 458. From his position on the crash line, Capt. William F. Greene, Medical Corps, sees the plane rise and disappear from view. After about half a minute, the co-pilot, Jennings, announces he is going to raise the lights. The AC notes an altimeter reading of 500 feet (240 actual) and calls for a reduction of the turbo boost setting to six. As the co-pilot starts to put his hand down to the controls, the crew experiences the sound and feeling of a bang or explosion as if blowing a blister. In the cockpit, the AC notices a flash of blue light reflected from the armor glass. Behind the co-pilot, FE Miller also notices the flash of light and starts to turn around to ask the pilot about it, but finds that he is still belted into his seat and cannot move, so he begins to make a check of his instruments: engine rpm is 2800 and manifold pressure is 50 inches, take-off settings. LG Warner calls to the right gunner without using the intercom, asking what the noise was. In the control tower, Cpl. Angelo sees a red flash come from aircraft 458. Fearing he may have lost an engine, AC Van Wingerden wants to turn to the engineer but keeps his eyes on his instruments: the gyro compass is not turning, and airspeed is between 150 and 155. Before he can check the climb indicator, there is a shudder followed by crashing. Flight Engineer Miller is thrown back against the armor plate. Left Gunner Warner grabs onto a bundle of wires above him, holding on while the aircraft is bouncing. One of the engines has gone through a tree, and the aircraft comes to a stop amid clumps of brush and trees, with flames breaking out. From his position on the crash line, Capt. Greene hears a dull thud and sees red flames shooting up into the sky. He heads for base to get an ambulance. In the control tower, Cpl. Angelo notes that just one minute has elapsed since take-off, and notifies crash crew, fire station, base operations, group operations, base commander, AACS office and provost marshal. Van Wingerden unfastens his safety belt and attempts to help the co-pilot, who appears to be unconscious and badly wedged in. Behind him, Miller tells him to get out quick, so the AC goes out through the nose, noting that the bombardier Woltz is not there. He has somehow gotten out of the ship. Miller tries once more to pull the co-pilot free, then goes through the opening in the nose after Van Wingerden. Meanwhile, LG Warner unfastens his parachute and tries to kick out the left blister, without success, so tries to go through the radar room, but is choked by smoke. As he backs up toward the right blister, he notices a hole in the ship forward of the right blister and dives out through it, head first. The pilot and the engineer are only about 15 steps from the aircraft, which appears to be engulfed in flames. They see no one else trying to escape. On the other side, the left gunner is running away from the ship. There is then a loud blast, and Warner falls to the ground. Van Wingerden and Miller are knocked flat. Flames and burning debris shoot into the air. From his jeep, Capt. David sees the flash of the initial explosion and hears the concussion. He turns his jeep toward the crash site, and hears another bomb explode as he nears the jungle area. About 150 feet from the plane, he finds the bombardier, Lt. Woltz, with a head injury and broken arm and leg. As Capt. David is administering to Woltz, another explosion occurs, sending a metal fragment across Davidís knee and leg. While David goes off to look for other survivors, Capt. Greene has arrived on the scene, and at 05:40, finds Van Wingerden and Miller about 200 yards from the wreckage. Shortly, the left gunner is found by other rescue personnel. These four survivors are sent to the hospital. The remaining seven menís bodies are identified. The bombardier, Lt. Woltz, succumbs from his injuries two days later. EPILOGUE The board of investigation, consisting of Col. William P. Brett, Lt. Col. Alvan N. Moore, Lt. Col. Winton R. Close, Capt. John Page, Capt. Edmund B. Sullivan, Capt. John L. Hardy and 1/Lt. Robert W. Libby, met on December 31st. The board determined that power was reduced either inadvertently by the co-pilot or by malfunction of the turbo system due to an electrical failure, causing an unexpected loss in power. A later review of these findings by headquarters, dated 24 January and signed by Brig. Gen. Roger M. Ramey, disagreed, stating that pilot technique was a contributory cause of the accident. It was noted that aircraft landing lights should have been left on longer, up to a full 500 feet of altitude. It was also noted that the pilot, probably inadvertently, reduced power at a dangerously low I.A.S. (150-155 mph), while stall speed of the B-29 is about 128 mph. The review considered it doubtful that an electrical malfunction could have caused all turbo waste gates to open abruptly. BOB SCHUMACHERíS MEMORY OF THE ACCIDENT Mark R. Miller wanted to share with the recollections of a fellow flight engineer of his dad's, Robert M. 'Bob' Schumacher, who witnessed the crash described in the original story. He emphasizes that "this is my personal opinion", but his explanation sounds very plausible in light of the fact that the engines were still running at full power when the ship hit the ground. Miller finds it interesting that the "official" report mentions nothing of what Bob remembers. Robert M. 'Bob' Schumacher:"I don't personally think the turbo waste gates had anything to do with the accident. Those gates controlled the amount of engine exhaust that was diverted to the turbo superchargers on each engine. They were controlled by electronics made by Minneapolis Honeywell and each engine had it's own control system." "Any airplane tends to rise a little as it approaches flying speed and often it will settle back a little and rise again as the lift increases. The B-29 had safety micro-switches to keep the landing gear from retracting while the struts were fully compressed while on the ground. Once the struts were fully extended, the circuits were completed so that the gear could be retracted." "Having been born and raised on a farm, I had a habit of getting up early. I used to like to go down to the base and crawl up into the radio operator's position and listen to BBC and/or Tokyo Rose. The morning of the accident was pleasantly cool (for India anyway) and very bright as I remember it." "On takeoff that morning all seemed normal but as the plane reached takeoff speed, the gear started to retract. The question arises as to whether there was a problem with the switch circuit (an electrical malfunction) OR was the "gear up" switch in the "up" position while the plane was still speeding down the runway (a serious error by the Co-pilot)? The plane settled back until the propellers hit the runway and all Hell broke loose." "The Co-pilot was responsible for raising and lowering the Landing Gear and Flaps on orders of the A/C. The big question circulating thru the squadron was whether or not the switch might have been placed in the gear-up position during the takeoff run with the idea in mind that when the struts extended, the gear would retract and thus speed up the process and aid in keeping the engine temperatures down." Sources: "Accident Reports" of Millville, NJ. Mark R. Miller, son of Uline C. Miller, flight engineer, 58W/444G/676S 444th Bomb Group |

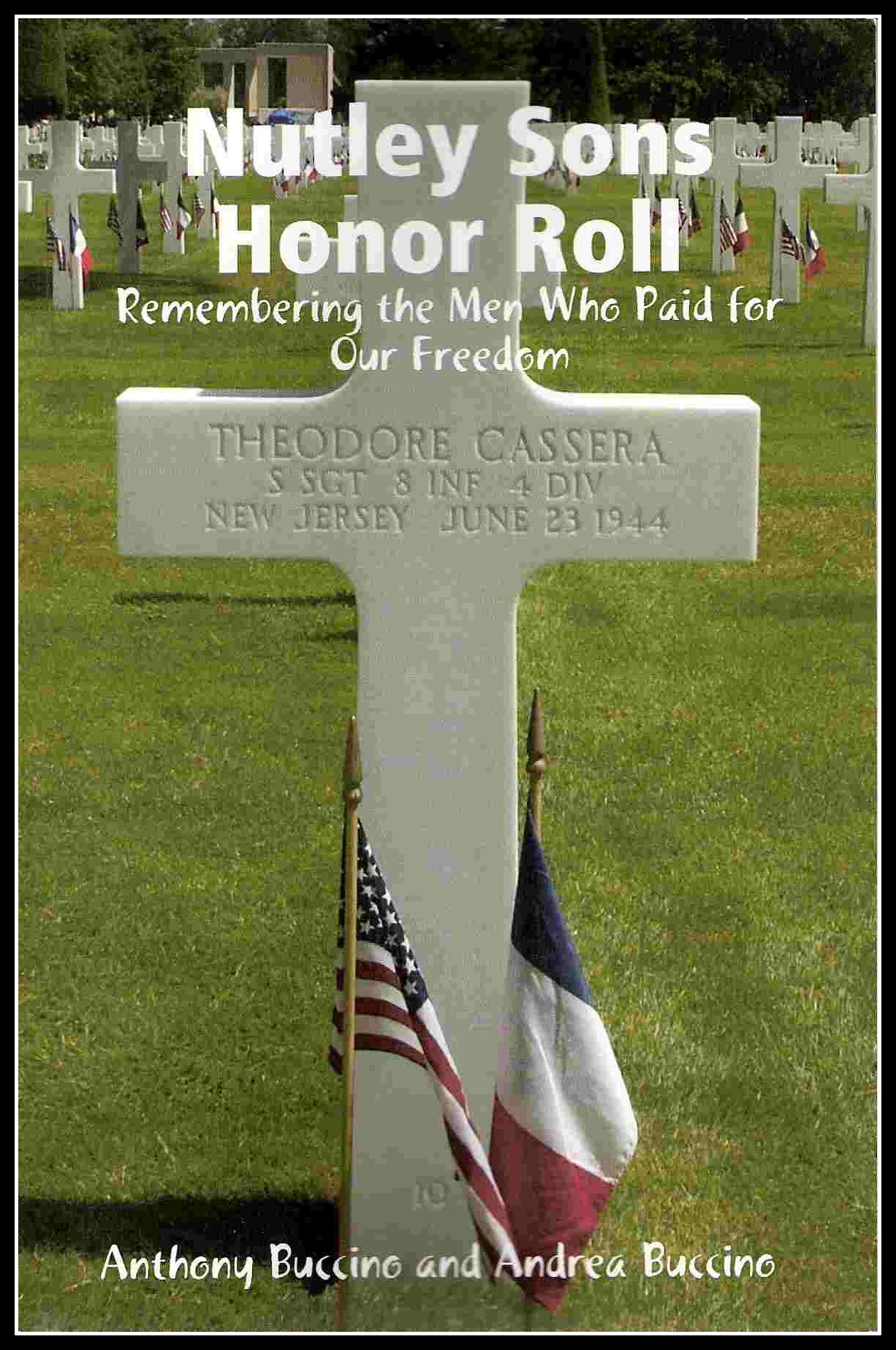

Nutley Sons Honor RollVietnam WarPeacetime CasualtiesKorean WarWorld War IIWorld War ICivil WarAmerican Revolution

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contact Us - Nutley SonsWeb site created by Anthony Buccino Snail Mail: PO Box 110252, Nutley NJ 07110 Entire contents NutleySons.com © 2001 by Anthony Buccino Web Site SponsorsREAD MORE: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||